Today’s “Puzzling” Consumer

This week I was chatting with a client, explaining how today’s consumer has more power than ever before: More information, more choices, more flexibility for exercising preferences, and most especially, less risk associated with changing their behaviors. It’s a theme people are already bought into — Forrester calls it the age of the customer — but it’s also a theme that people are too quick to believe they understand without grasping the kinds of changes this requires for a business to serve such an empowered customer. To get to that extra level of awareness, during my conversation this week, I came up with a way to describe it that I call the puzzling consumer.

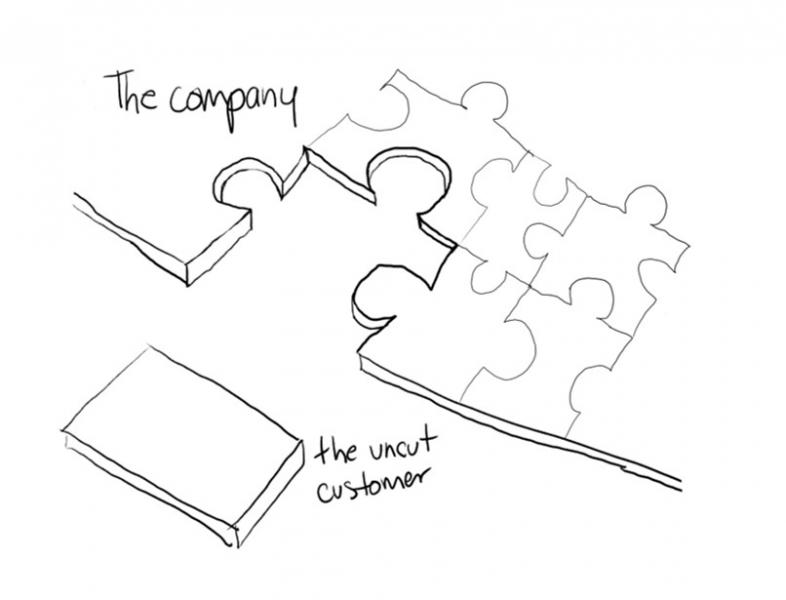

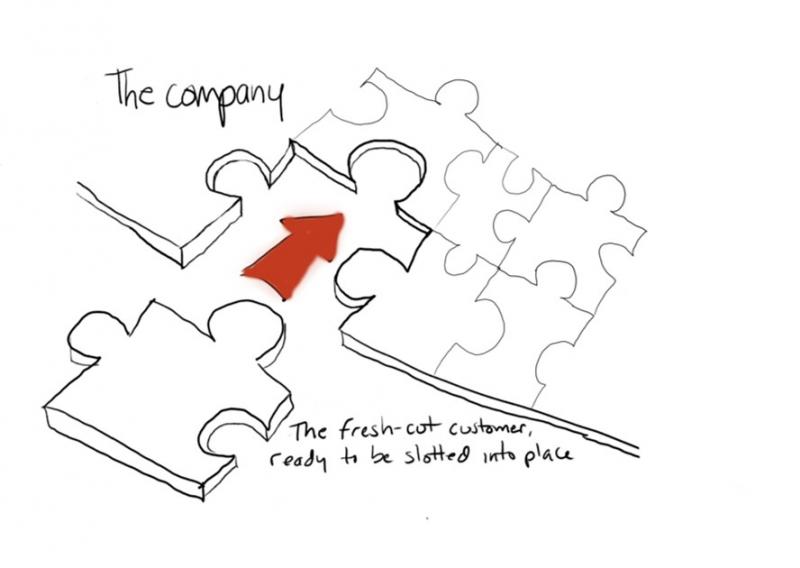

Back in the day, a company designed a puzzle for you and saw you as a missing piece. They defined a hole with a certain shape, one that was convenient to them based on the analog tools they had, the historic mindset of their industry and so on. Then the company invited you to reshape yourself to fit that hole.

And you did, we all did. To use a retail example, we heard about a store like Circuit City, we figured out where it was located, looked up a phone number to call and find out when the store was open and if they carried the boomboxes we were interested in (that phone call was always a disaster, but I digress). We drove by there on a Saturday morning, parked in the parking lot they designed, walked into a retail space they had configured for their purposes (TVs in the back, to make you walk all the way through the store), and were ambushed by a salesperson who pretended to know a lot about the products involved even though he (and it was typically a he) was just reading the same product pamphlets that we could read if we wanted to.

By the time we bought that product from Circuit City, we had jigsawed ourselves to fit their specific needs. Having done that, we were customers of theirs and barring any dramatic disappointment, we were likely to prefer that company, that store, maybe even that salesperson, Stockholm-syndrome like, because we would rather keep putting ourselves into their jigsaw puzzle than to have to cut ourselves into a completely new shape. That’s the cost and risk associated with behavior change in an analog era. And it’s why we were stubbornly loyal to so many companies back then. The same is true for retail banks, health care providers, cable providers, and to a large extent consumer products, too. The famous give-the-razor-sell-the-blades model is a literal version of the situation I’ve just described: The razor has a shape into which only specific blades can fit.

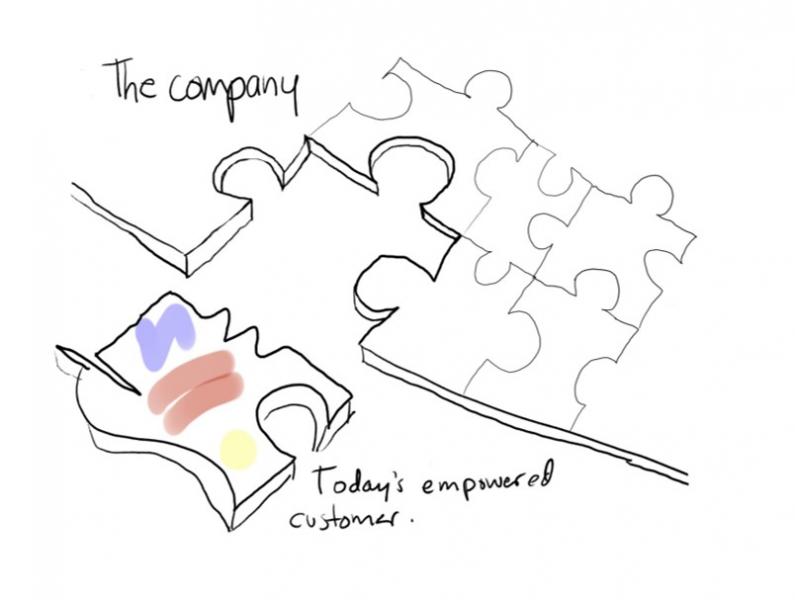

These jigsaw puzzle days are over. We no longer have to cut ourselves to fit into the jigsaw puzzles designed by the corporations around us. I take whatever shape I want, I can even morph my shape if I want. And I don’t just want the company to respect who I am, I want it to fit in around me! I want it to redesign the entire experience of the brand and the service to snugly fit even the most challenging of my personal contextual contours. If they don’t, someone else will, I’m sure of it.

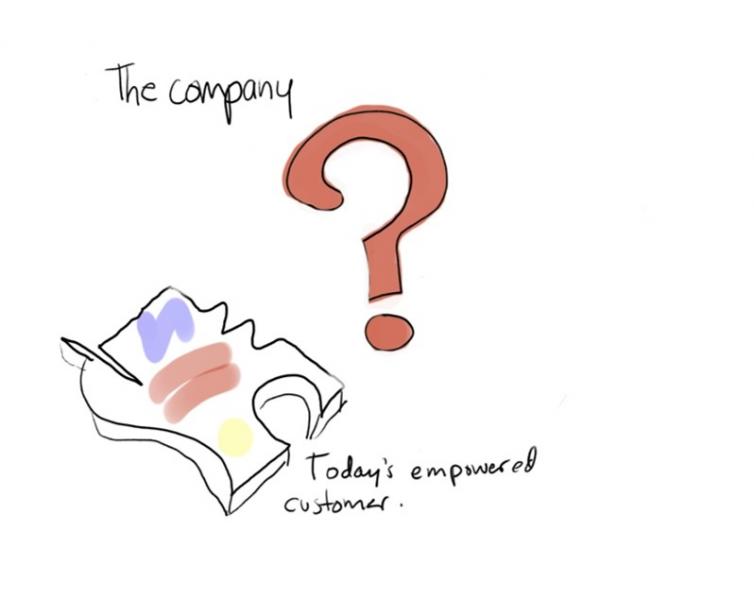

That’s what makes the puzzling consumer so, well, puzzling. You have to give up thinking you can own them ever again, that part is obvious. But you also have to give up thinking that you own yourself, too. Your experience is now theirs. They own it: They participate in its design, they choose their path through it, they share their satisfaction and their dissatisfaction online, and they ultimately value you based on how much work you did to serve them rather than the other way around. So what happens to your side of the puzzle?

That’s what digital disruption is about. You’re not just using digital tools and solutions to make your company — your side of the puzzle — more efficient. You’re not just on the hook for product innovation or even customer experience improvement. You have to rethink the shape of your organization: Who you are, how you are organized to connect to that customer, learn about them, and deliver them value. The entire operating model changes. It takes a different kind of leader, too. You can’t be the piece of the puzzle tucked away in the static corner office anymore. You have to connect the various pieces of your organization, marshal their energy and resources to adapt to serve. It will be challenging — we call it disruption for a reason — but it will be exhilarating, too.

_______

James McQuivey, Ph.D., is a vice president and principal analyst at Forrester. He is also the author of the book Digital Disruption.